“There are songs from the past that I no longer feel comfortable singing,” Gilmour says. “I love Run Like Hell [from 1982’s The Wall]. I loved the music I created for it, but all that (sings) ‘You’d better run, run, run…’ I now find that all rather, I don’t know… a bit terrifying and violent.”

Certainly! Here’s a 800-word elaboration based on the quote you provided:

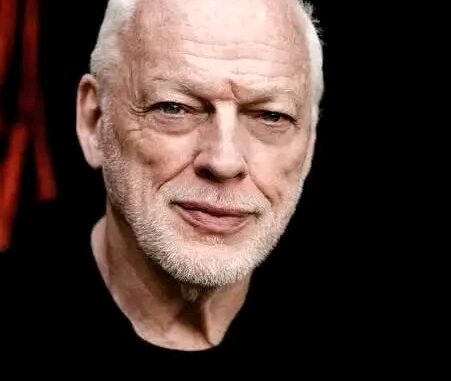

David Gilmour, legendary guitarist and vocalist of Pink Floyd, has often reflected on the evolution of his relationship with the music he helped create. In a candid moment, he shared, “There are songs from the past that I no longer feel comfortable singing.” This statement reveals a deep, personal shift—one that many artists experience after years of performing the same material. Gilmour’s words about “Run Like Hell,” a track from Pink Floyd’s iconic 1982 album *The Wall*, offer a window into how perceptions of art can change over time, especially when considering the themes and emotions embedded within the music.

“Run Like Hell” is known for its driving rhythm, an urgent guitar riff, and a chorus that emphasizes fear, pursuit, and a sense of urgency. The song’s lyrics, “You’d better run, run, run,” evoke imagery of escape and paranoia—fitting with the album’s overarching themes of alienation, control, and societal pressure. When Gilmour says he loved the music he created for it, he acknowledges the craftsmanship and the energy that went into composing and recording the song. Yet, his discomfort with singing it now hints at how the emotional impact of the lyrics and the mood they project can evolve, sometimes becoming unsettling or even disturbing.

This shift in perspective is not uncommon among artists. Over the years, personal growth, changing societal values, and increased awareness of the implications of certain themes can alter how one relates to their earlier work. For Gilmour, the phrase “a bit terrifying and violent” suggests that, upon reflection, the song’s aggressive tone and the imagery of fleeing or being chased now strike a chord that feels darker or more unsettling than it did at the time of release.

It’s important to understand that the themes of “Run Like Hell”—fear, persecution, and the desire to escape—are rooted in a context that can be interpreted in multiple ways. Originally, it might have been viewed as a reflection of personal or societal anxieties, or even an energetic expression of rebellion. However, with time, the lyrics can take on a more visceral meaning, perhaps resonating with feelings of threat or violence that are more immediate or personal to the listener or performer.

Gilmour’s feelings highlight a broader phenomenon: the way art is not static but fluid, capable of accruing new meanings as circumstances and perspectives change. Songs that once felt empowering or cathartic might, over time, feel raw or uncomfortable. This is especially true when the themes involve fear, violence, or trauma, which can evoke strong emotional responses. As an artist matures and gains life experience, what once seemed like a powerful statement might come to feel like a reminder of darker times or uncomfortable truths.

Moreover, Gilmour’s honesty underscores the responsibility and vulnerability that come with performing certain material. Artists often grapple with the emotional weight of their songs, especially those that deal with intense or disturbing themes. Singing “Run Like Hell,” with its aggressive tone, may now evoke feelings of discomfort or even guilt if it brings back unsettling memories or feelings. It raises questions about whether artists should continue to perform material that no longer aligns with their current emotional state or personal ethics.

This phenomenon also touches on the broader cultural and social implications of art. Songs that once seemed to celebrate rebellion or assertiveness can, over time, be reinterpreted or viewed through a different lens—sometimes as promoting violence or fear. As society becomes more aware of issues like violence, mental health, and trauma, artists and audiences alike may reassess the messages conveyed by certain works. Gilmour’s discomfort with singing “Run Like Hell” reflects this ongoing dialogue between the artist’s intentions, the audience’s interpretations, and the evolving societal context.

Interestingly, this change does not diminish the artistic value of the song or its historical significance. Instead, it exemplifies how art continues to live and breathe, capable of eliciting different responses at different times. For Gilmour, choosing not to sing the song anymore may be a way of respecting his current emotional boundaries and acknowledging the complex feelings that certain works evoke in him now. It also illustrates a kind of artistic integrity—recognizing that, as humans, our perceptions and sensitivities evolve, and that our relationship with our creations can shift accordingly.

In conclusion, Gilmour’s reflection on his discomfort with singing “Run Like Hell” is a poignant reminder of the dynamic relationship between artists and their work. It highlights how personal growth, societal change, and emotional sensitivity influence our connection to art over time. While the song remains a powerful and influential piece of rock history, Gilmour’s feelings reveal that even the most iconic works can become complex and nuanced as we navigate our own journeys. Ultimately, it underscores that art is not just a reflection of the past, but an ongoing conversation—one that continues to evolve as we do.

—

Would you like me to expand further on any specific aspect or provide a different style?

Leave a Reply